Repercussions on the Netherlands of Indonesian Independence

SUMMARY:

The granting of independence to Indonesia, by freeing the Netherlands from its major military commitments in the archipelago, should enable the Dutch to concentrate on metropolitan defense and contribute more effectively to Western European joint defense efforts. The loss of Indonesia may weaken Dutch support of the colonial position of other European powers. Expansion of Dutch economic relations with other areas, including the Western European countries, is expected to result from the loosening of economic ties with Indonesia, and may lead to more active Dutch participation in the European integration measures which the US favors. Although there is considerable latent Dutch resentment toward the US for its positive role in the negotiations leading to Indonesian independence, this has not seriously impeded Dutch support of other US policies and objectives.

Indonesian independence, achieved in December 1949, has brought numerous problems to the Netherlands. Under the new political relationship – an equal partnership in a commonwealth-type union nominally headed by the Dutch monarchy – some of the earlier frictions persists. Another important problem still unsettled is the future status of Netherlands New Guinea, which the Netherlands is reluctant to cede to Indonesia despite the demands of Indonesian leaders. In addition, involvement of Dutch nationals in dissident Indonesian movements will antagonize the Indonesian Government and arouse suspicion of the motives of the Netherlands Government. On Far Eastern questions, the position of the Netherlands is likely to be dictated primarily by its own interests, though it will not alltogether disregard the policies of Indonesia.

Some divergencies have already developed, as illustrated by the Dutch recognition of the Bao Dai regime in Indochina, a regime which Indonesia does not acknowledge, and by Dutch support of the UN in the Korean conflict, concerning which Indonesia proclaimed itself neutral.

Within the Netherlands, criticism of the Government’s Indonesian policy is likely to continue. It is unlikely, however, to threaten the stability of the government unless concessions to Indonesia on New Guinea are carried to the point of eliminating Dutch sovereignity in that area.

Before the war, Indonesia was a very important economic asset to the Netherlands. The area gave the Dutch primary access to a rich variety of natural resources. This was of particular importance because of the very limited resources of the metropolitan country. Possession of Indonesia guaranteed to the Netherlands supplies of many essential tropical products, and the sale of these to foreign countries was a source of foreign exchange. The development of Indonesia provided a profitable outlet for Netherlands capital. As a result of the extensive destruction of property during World War II and the subsequent Netherlands-Indonesian conflict, the postwar economic contribution of Indonesia to the Netherlands was very limited.

Although te granting of independence resulted in no immediate economic injury to the Netherlands, the effects are now beginning to be felt, and may be expected to increase in future years. Present Dutch investors in Indonesia will probably suppy the necessary capital to repair wartime damage and restore prewar production levels. This will keep capital moving from the Netherlands to Indonesia for possibly several years. During this reconstruction period the Netherlands Government will probably continue the extension to Indonesia such credits as are necessary to maintain financial and commercial relations between the two countries.

- Note: The intelligence organizations of the Departmens of the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force have concurred in this report; for a dissent by the Intelligence Organization of the Department of State see Enclosure. This report contains information available to CIA as of 17 November 1950.

The return of Dutch civilans and troops from Indonesia is proceeding rather rapidly, and the need for manpower is such that no unemployment is anticipated. There will be a very sharp decline in personal remittances to the Netherlands from Indonesia. The cancellation by the Netherlands of 2 billion guilders of the Indonesian debt will result in another sizable loss of income.

The major long-run economic effect of Indonesian independence will be the loss of an attractive field for the investment of Dutch capital. Discrimination by the Indonesian Government against Dutch investments is forbidden by treaty but an anticipated increase in government controls, higher wages, and continued sporadic lawlessness will make it more and more difficult to attract Dutch capital.

The reduction of Dutch military commitments in the Far East will nog immediately increase Dutch millitary capabilities in Europe, as the latter presently depend more upon the provision of equipment and instruction than upon manpower. The Netherlands Army personnel returned form Indonesia will be utilized largely in reserve units. Comparatively few of the former members of the Netherlands Indies Army and Air Force are likely to enter the Dutch metropolitan forces. Since an over-all reduction in navy personnel has been taking place, repatriation will have little effect on Dutch naval strength.

Introduction.

Dutch political control in Indonesia, as well as the prewar economic benefits derived from it, was never fully restored after World War II. Even if Indonesia had not gained complete independence, the force of the nationalist movement would have reduced Indonesia’s prewar economic importance to the Netherlands. Though it is too early to evaluate the effectiveness of the dominion-type of relationship which has replaced colonial control, the large Dutch economic holdings remaining in Indonesia guarantee that the Dutch will continue their efforts to maintain influence in the former colony and to establish close and permanent working relations with it. Nevertheless, the international position of the Netherlands has been considerably altered and its strategic interests in the Far East have been reduced by the granting of independence to Indonesia on 27 December 1949. By relinguishing political, economic and military control of the archipelago, The Netherlands lost political direction of the exploitation of the resources in Indonesia.

Effects on US Interests.

Although there is considerable latent Dutch resentment toward the US for its positive role in the negotiations leading to Indonesian independence, this has not seriously impeded Dutch support of other US policies ond objectives. There is no reason to believe that future Indonesian developments will have an adverse effect on Netherlands-US relations.

With the major Dutch military commitments in Indonesia terminated, the Netherlands will be able to contribute more effectively to Western European joint defense efforts, thereby utilizing US military aid more efficiently. Loosening of economic ties with Indonesia may be expected to result in expansion of Dutch economic relations with other areas, including the Western European countries.

This would in turn stimulate more active Dutch participation in the integration measures which the US considers essential for a healthy Western European economy.

The drain on the Netherlands economy occasioned by the costly postwar conflict in Indonesia was indrectly eased by US aid through ECA. However, that drain is still being felt during 1950 because of the expense of withdrawing Dutch Troops from Indonesia. If Indonesian efforts to achieve economic independence curtail the Dutch role of intermediary in exports from Indonesia tot the US, the Netherlands problem of meeting its dollar payments will become more serious.

1. Political repercussions

Dutch-Indonesian Political Relations.

The Hague Agreements establishing an independent United States of Indonesia and the Netherlands-Indonesian Union were reluctantly accepted as inevitable by the majority of the Dutch people. Although the Dutch Government has made some progress toward closer cooperation with Indonesia, a number of problems have arisen since early 1950 which have unfavorably affected Netherlands-Indonesian relations. Difficulties in implementing The Hague Agreements have been largely due to inability of many Dutch to forego the role of colonials and of ultra-nationalistic Indonesians to accept the important economic position of the Dutch in the Islands. Support given dissident Ambonese and other Indonesian elements by Dutch nationals has aroused considerable Indonesian antagonism against the Netherlands Government and directed suspicion toward the Netherlands remaining in Indonesia. The current status of relations between the two countries would indicate that the daily working relationship established between the respective High Commisioners and Governments will be more important in determining good will and cooperation than the formal structure of committees and conferences between the two governments, at least until Indonesia is firmly oriented toward the West. The Indonesian Goverment’s efforts to minimize the influence of the Union upon its foreign and economic policies probably will continue. Untill the new nation has reached such political maturity that it no longer feels the need to prove its independence of action and its equality and untill the Dutch cease to think of Indonesia in terms of its former subordinate position, Indonesian leaders will not place much trust in the efficacy of the Union to solve their problems.

The most serious political problem is the future status of Netherlands New Guinea, which is to remain under Dutch control until the end of 1950. With both Indonesia and the Netherlands unequivocally claiming the right possession of the area, a resolution of the issue will be dificult to achieve. The two governments are determined, however, to prevent third-party or international intervention in negotiations on the question, at least until serious efforts to reach agreement have been made a special conference to be held in late 1950.

A large minority in the Netherlands, which includes Labor Party members and businessmen with extensive Indonesian holdings, formerly believed that it was best to relinquish New Guinea to Indonesia. The recent outbreak of fighting on Ambon, however, has considerably increased the support of these elements for the Government policy of maintaining Dutch authority in New Guinea. The primary factors put forth in arguments against the present Dutch position are:

- Indonesian threats of reprisals against Dutch property in Indonesia if New Guinea is not ceded;

- the damage, perhaps irreparable, to the functioning of the Netherlands-Indonesian Union;

- the financial burden to the Netherlands that the development of New Guinea represents.

The Government is unlikely to change its present stand in the initial negotiations, however, and if no compromise agreement is forthcoming, will press for the postponement of a final decision and the continuation of Dutch control in the area in the interim. Neither Government favors joint control or any kind of trusteeship for New Guinea. Even if agreement on a solution of this sort could be reached, some dessatisfaction on both sides would be evident and would, at least for a time, hamper cooperation on other problems.

Dutch International Relations.

Although the new status of Indonesia has had no direct visible effect on Dutch foreign policy as it relates to Europe, it has promoted the increasing Dutch preoccupation with European affairs. The new status of Indonesia may also weaken Dutch support of the colonial policies of other Western European powers, with which Dutch policies had been closely associated. If so, the Dutch attitude would not be dictated so much by bitterness over the loss of Indonesia, as by an increased necessity for maintaining good relations with Indonesia and the Caribbean territories.

With regard to Far Eastern questions generally, the Dutch position will be dictated primarily by the Netherlands’ own interest. The Dutch have agreed to consult with the Indonesians on matters of foreign relations, but are not committed to a common policy. The readiness of the Dutch to pursue an independent course was demonstrated by The Hague’s recognition of Communist China, prior to Peiping’s recognition of Indonesia, and of the Bao Dai regime in Indochina, which Indonesia has not recognized. The Netherlands also gave full support to the UN Security Council resolution on Korea, whereas Indonesia officially adopted a neutral attitude toward the Korean conflict.

Dutch Colonial Relations.

The establishent of Indonesian independence has encouraged the Netherlands Antilles and Surinam (Dutch Guiana) to ask for a greater autonomy within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The Dutch have already gone part way by providing an interim administration for the West Indies with independence in internal administration and respresentative assemblies for the various islands, in preparation for an eventual constitutional revision providing Surinam and the Antilles with ‘equal’ status with the Netherlands in the Kingdom. Although these measures have not satisfied the representative of the Caribbean territories, they open the way to further concessions. It is possible that the Netherlands will endeavor also to have its Carribean possessions represented in the Netherlands delegation in The Netherlands-Indonesian Union, although during the Dutch-Indonesion negotiations, Surinam and Curacao expressed opposition to their inclusion within the Union. Besides these political measures, the Netherlands will now show a greater interest in the economic development of the West Indies, particularly if New Guinea is lost.

Dutch Domestic Politics.

The granting of Indonesian independence practically ended political dissension in the Netherlands on that fundamental question, although criticism of the evolution of working relations with Indonesia will continue. The opposition of the rightist parties was revealed recently in parliamentary criticism of the government’s passive attitude toward Indonesian moves to replace, with a unitary state, the federal structure established by The Hague Agreements. Thsi criticism indicates the strong stand that may be expected against any concessions on New Guinea. The stability of the government is not likely to be threatened by this question, however, before late 1950, and then only if the governmental parties are unable to agree on a policy regarding New Guinea. Otherwise, the present coalition will probably continue until after the next national elections in 1952.

2. Economic Repercussions.

Importance of Indonesia to the Netherlands.

Through its former control of Indonesia, the Netherlands gained a first claim to access to Indonesia’s rich natural resources. These resources provided extensive opportunities for skilled Dutch enterprise as well as an economic frontier into which Dutch capital could move with the assurance of legal protection and the opportunity for realizing large profits. As the Indonesian economy expanded, it constituted an increasingly important market for Netherlands industrial products and for the service of its merchant fleet, as well as providing employment for trained administrators and technicians from the Netherlands. In the Netherlands itself, some manufacturing industries were partly dependent upon Indonesian raw materials. Extensive banking and commercial activities were established or expanded on the basis of the dominant Dutch role in the Indonesian economy. It has been estimated that in prewar years about 15 percent of the Netherlands national income was derived directly or indirectly from possesion of Indonesia. Those benefits were of particular importance to the Netherlands because of the very small size and limited resources of the metropolitan country.

Furthermore, the Netherlands was able to meet its payments deficit with other countries with foreign exchange earned by Indonesia. Indonesia had a surplus on current accoutn with other areas but a deficit with the Netherlands. Thus, in prewar years, metropolitan Netherlands and Indonesia taken together were in long-term payments equilibrium with the rest of the world.

Investments.

Before the war, 39 percent, or apporximately the equivalent of $2 billion, of the total Dutch foreign investments were in Indonesia. In the three-year period, 1937 through 1939, about 47 percent of the Netherlands total foreign investment revenues were received annually from the Netherlands enterprises operating in Indonesia. It is evident, therefore, that the rate of investments in Indonesia was considerably greater than the reat of return from Netherlands investments in other parts of the world. As a result of destruction and plunder during the Japanese occupation and during the postwar conflict, Dutch properties in Indonesia sustained very serious damage and the delay in reconstruction caused further losses.

The postwar investment losses in Indonesia are even more serious for the Netherlands in view of the simultaneaous reduction of income from other areas. As one of the leading creditor countries before World War II, with extensive investments in all parts of the world, the Netherlands suffered losses not only in Indonesia but in other areas as well. In addition to heavy losses in Europe, the Netherlands has found it necessary to liquidate about $265 million of its dollar assets since 1945 in order to meet current dollar payment deficits. Although the Netherlands has retained its international creditor position in the postwar period, total current revenues acrruing to the Netherlands from interest, dividends, and profits form abroad are lower than in prewar years, and probably will be reduced further as additional foreign loans are obtained.

Under the provisions of The Hague Agreements, Netherlands investors retained their holdings in Indonesia after independence was granted, and the change in juridical status had, of itself, little immediate effect on the value or earnings of Netherlands investments. Discrimination against Dutch investments is forbidden in treaty. There has been no nationalization of basic industries, although the inter-island airlines have been brought under Government control, and similar controls are anticipated with regard to inter-island shipping.

Present conditions in Indonesia are not such as to encourage new Dutch investments. Political uncertainty and continuation of sporadic lawlessness have had an adverse effect on the development of Dutch investment and profits. Moreover, the Indonesian Government in March 1950: (1) reduced liquid assets by 50 percent through a currency conversian; and (2) introduced foreign exchange measures which resulted in tripling the cost of imports for rehabilitation and expansion purposes and in increasing the cost of remitting dividends abroad.

At the same time, however, these new regulations stimulated the export of Indonesian raw materials, a large proportion of which are derived from Dutch-owned properties and therefore served to maintain the level of Dutch earnings. No serious reduction in profits is expected to result in the near future from the wage rises granted since independence, because export prices on such essential items as rubber and tin have increased considerably owing to the rearmament needs of the West. The Indonesian Government aims eventually to institute state control of the privately-owned public utilities and transportation systems, and possibly of other vital branches of production and natural resources. These developments will cause future difficulties for Dutch investments.

The Indonesians, however, depend to a great extent upon foreign investment, of which about 70 percent was Dutch before World War II. This need for foreign capital will certainly continue for many years because of the low level of Indonesian private saving. It is probable, therefore, that a large sector of the economy will be permitted to remain in foreign hands for a considerable period.

Netherlands trading and financial interests constitute an integral part of the Indonesian economy, and although there has been some effort on the part of the Indonesian Government to promote the interests of Indonesian traders, it probably would take years for these newcomers to compete effectively. The political and economic uncertainties which Indonesian independence has brought will tend, at least for the present, to discourage Dutch investors from initiating new enterprises, even if capital is available. Investments probably will be confined to existing enterprises to restore normal production.

Dutch Budgetary Expenditures.

Because of expenses assumed as a result of Indonesian independence, the Netherlands 1950 budget deficit, originally 410 million guilders, has been increased by about 160 million guilders. After 1950 there will be reduced expenditures, however, particularly on the training, supplying, and transport of troops to Indonesia, items which entailed large expenses in previous years. (Expenditures for Dutch troops actually in Indonesia were in the paste borne largely by the Dutch-controlled Indonesian Government). If the Netherlands retains control of New Guinea, future capital expenditures for the economic development of the area and the expansion of military installations probably will be increased, offsetting to a certain extent the reduction in expenses for Indonesia. By its cancellation of 2 billion guilders of the Indonesian debt, the Netherlands will sustain an annual loss of roughly 110 to 125 million guilders in interest and amortization, assuming the debt would have been retired over a 25-year period as the Netherlands Government had proposed before this cancellation.

Invisible Payments and the Indonesian Debt.

Postwar earnings from Dutch loans to Indonesia and from investments in the Archipelago have been maintained at a fairly satisfactory level, considering the extensive destruction in Indonesia and the low rate of production.

This was accomplished, however, only by the extension of Dutch guilder credits by the Netherlands Government to the Indonesian Government. By the end of 1949, the Indonesian debt to the Netherlands totaled about 3 billion guilders. At the Round Table Conference, the Netherlands agreed to cancel 2 billion guilders of the debt, representing mainly the obligation incurred during and after World War II. The Netherlands Government has agreed to extend a credit of 200 million guilders to Indonesia during 1950, a sum expected to cover about two-thirds of Indonesia’s invisible deficit with the Netherlands for the year. The remaining third is to be covered by hard currencies or through providing the Netherlands with hard currency exports over and above the exports provided for in the Netherlands-Indonesian trade agreements.

The transfer of interest and dividends earned in Indonesia to the Netherlands will constitute a problem for some time. During the next few years credits probably will be needed if the Indonesian Government is to continue to meet its deficit on invisible account with the Netherlands. It appears probable that an arrangement will be made during the next few years similar to that provided for in 1950.

Next see pdf: Download pdf link for CIA document.

“Trade

Industry

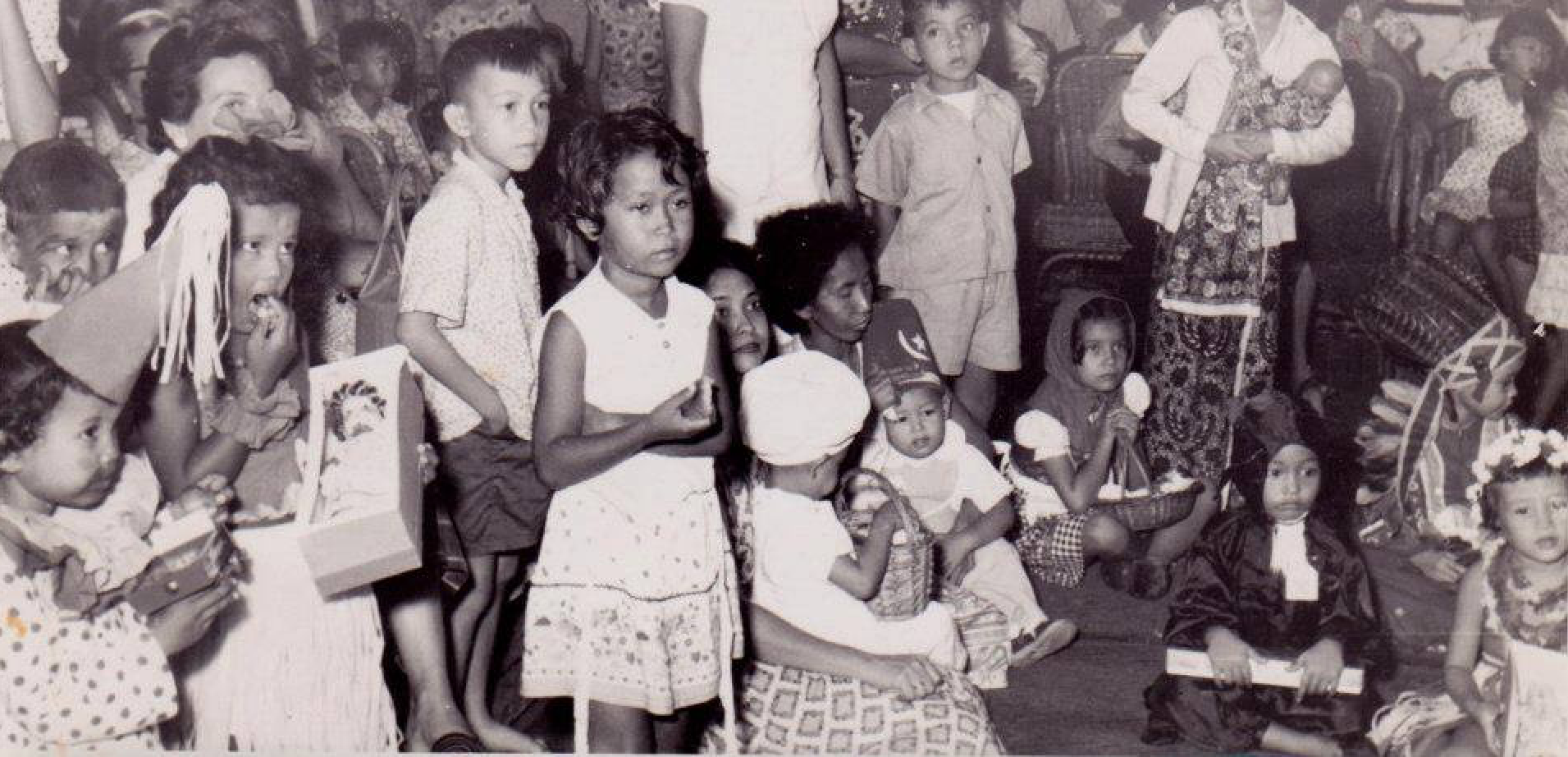

The Dutch in Indonesia

Military Repercussions”

Wiki: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Central_Intelligence_Agency

#indischekwestie